![]()

It’s true that Sir Francis Drake had his share of critics. Some said he didn’t always fully take or respect the advice of those around him. Some of the ship’s officers didn’t like the fact that he frequently talked directly to the crew (bypassing them). There were those who were at times offended by the directness in his critique of them and some who found him somewhat vainglorious about his achievements. Many of wealth and power felt that because Francis Drake had not come from royal blood (a disputable claim on one side of his family) and because he was raised a shepherd and a common sea trader, he had no right to accept and realize a command comparable or above that of any of his superiors. There were also a few incidences and missions very late in Drake’s career that showed him (not always by his hand) to be less than the invincible and infallible “El Draque” (the Dragon) that the Spanish had long learned to fear.

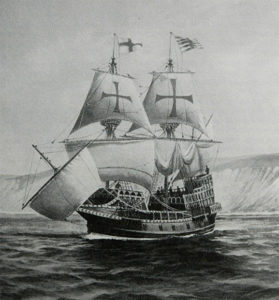

And the fear shared by the Spanish was not without good reason. Throughout Drake’s illustrious career, he made many successful land and sea raids in the Caribbean beginning with his attack in Panama on the treasure port, Nombre de Dios, and the very profitable mule train raid nearby in the years 1572-73. His circumnavigation of the globe (1577-1580) is, of course, legendary. In 1585, Francis Drake was ordered by Queen Elizabeth I to lead an expedition to attack Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. He was put in command of twenty one ships with 1,800 soldiers. Drake’s fleet captured Santiago in November 1585; won the Battle of Santo Domingo to capture the city in January 1586; won the Battle of Cartagena de Indias to capture the city in February; and raided the fort of St. Augustine (Florida) in July. On the return leg of the voyage, he rescued colonists from Roanoke, Virginia, the first organized English settlement in the New World. The following year (1587), Drake boldly conducted an important preemptive raid at Cadiz, Spain where he reported to have “singed the king’s beard” by burning some 28 ships and postponing the attack on England by the Spanish Armada by a full year. That following year, (then Vice-Admiral) Drake’s idea, shared with Lord Admiral Charles Howard, to use “fire ships” against the Spanish fleet’s anchorage near Calais, France was key to the success of breaking up and defeating the largest group of warships ever assembled to that day, when the Spanish Armada amassed some 140 ships (with some 2,400 pieces of ordnance and 30,000 men) in the English Channel in 1588.

Although Francis Drake’s first captainship was in assistance to his cousin John Hawkins’ moving of African slaves to Spain’s New World, I’d like to note that Drake later befriended many runaway slaves, known as the “Cimarrones” in Panama during his raid on a Spanish mule train in 1573. One of those men, a man named Diego, became a trusted friend of Drake’s for many years. He was with Drake during his voyage of circumnavigation that brought him to Marin County. Later, Francis Drake was one of the very first ship captains to bring black seamen aboard his ships with the promised commitment of “equal pay for equal work”.